Buffalo Newsboys

"Newsboy", painting by Thomas LeClear. Image source: AKAG

The phenomenon of children selling newspapers is an American and British invention. As Buffalo artist Thomas LeClear shows us, Buffalo had newsboys in the 1850s. Children (nearly all boys) who sold newspapers were an easily exploited source of labor. They bought the newspapers they sold, which inspired them to try harder to sell them to passersby on the downtown streets, on the streecars, and in the saloons. There were no laws of any kind restricting child labor in the 19th century.

Some children were sent to the streets to sell papers or shine shoes by family members who needed the income to supplement their impoverished existence. Other children eagerly sought out the jobs to acquire money of their own. The youngest children, sometimes as young as 6, often sold more papers because pedestrians bought their papers out of pity. A small percentage of newsboys were homeless, having been abandoned by their parents or run away from home, both made easier by the hubbub of the Erie Canal terminus in the city.

During the long hours they spent on the streets each day, newsboys were at risk of assaults by other newsboys or adults; this included sexual assaults. They became ill. They also learned to steal, swear, beg, and gamble. There seemed to be no help for children like these who had no hope of an ordinary childhood. The newspapers and distributors regarded them as 'little businessmen' and had no reason to look after their welfare. A general opinion was that schooling was wasted on working-class children because they could gain any needed skills while actually working.

Things changed in Buffalo in 1872, when David Brown, president of the Young Men's Association of the Grace Methodist Episcopal Church, organized a Thanksgiving dinner for newsboys and bootblacks. Assistance from Buffalo luminaries was swift from people like Millard Fillmore, George Clinton, Pascal Pratt, William P. Letchworth, etc. That dinner served 180 hungry boys and prompted Letchworth to initiate a project to find a home or shelter for the homeless boys among that group.

Bootblacks' Home, 29 Franklin St. Image source: BECPL

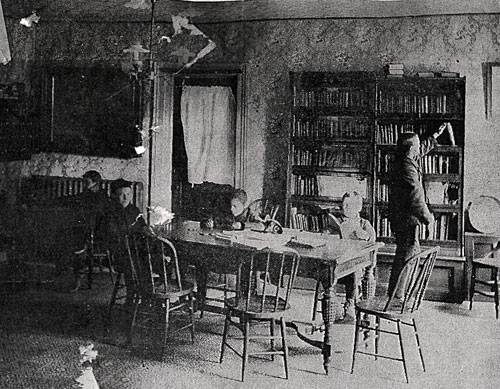

The next year, the Buffalo Children's Aid Society was founded with Letchworth as its president. The organization purchased an old house at 55 Pearl St. Shortly, and an army of women volunteers stepped in and organized the facility. The Newsboys' and Bootblacks' Home moved to a larger building at 29 Franklin Street in 1885. It was across the street from police headquarters and offered 40 beds to boys from 10 to 18 years of age (in 1890 it was ages 5 to 16). Its matron since 1884 was Miss Coke, an Englishwoman who maintained high standards of cleanliness.

She replied to a reporter's query if she found new admissions to be dirty upon arrival: "Dairty!" she exclaimed with quaint accent, her brown eyes twinkling. "Why we have to hasten them to the bath-toob so fast as ever we can. And boogs! My,my! I never saw so many boogs in all my life. Sometimes they're fairly crawling with'n, so I have to burn thier clothes. They can't go to bed without they're clean. No, no."

She replied to a reporter's query if she found new admissions to be dirty upon arrival: "Dairty!" she exclaimed with quaint accent, her brown eyes twinkling. "Why we have to hasten them to the bath-toob so fast as ever we can. And boogs! My,my! I never saw so many boogs in all my life. Sometimes they're fairly crawling with'n, so I have to burn thier clothes. They can't go to bed without they're clean. No, no."

There were strict rules in force which reduced the number of homeless boys willing to reside at the Home. The boys had to be in bed at 10 p.m. except on Saturdays when they could stay out until 11 p.m. (which most did). They had to attend an evening school, a Sunday school, and no tobacco, liquor or bad language was permitted. The boys paid $1.75 a week for their lodging.

The Home established savings banks for each resident, with deposits optional on the part of the boy. If $5 was accumulated, a bank account was established for the boy with the stipulation that he not withdraw the money for three months.

Sometimes, infants and women young and old turned up looking for assistance. Some boys were brought in as an alternative to abusive homes. The children who had lived on the streets for years were challenging to manage in a structured environment.

"Sometimes" said the Matron, "I get almost discouraged with'n, they give me such back-talk. But who could blame'n for being saucy? They didn't have anybody to start'n right"

Reading room at the Bootblacks' Home. Image source: BECPL

The library had the popular "Ragged Dick" and Oliver Optic books but also collected what donors no longer wanted and which went unread by the boys.

The Home claimed much success in its program. One wall was covered with before-and-after photos of boys who had passed through the Home and on to a better life. The Newsboys' and Bootblacks' Home would continue until 1926 when other social service options came into being.

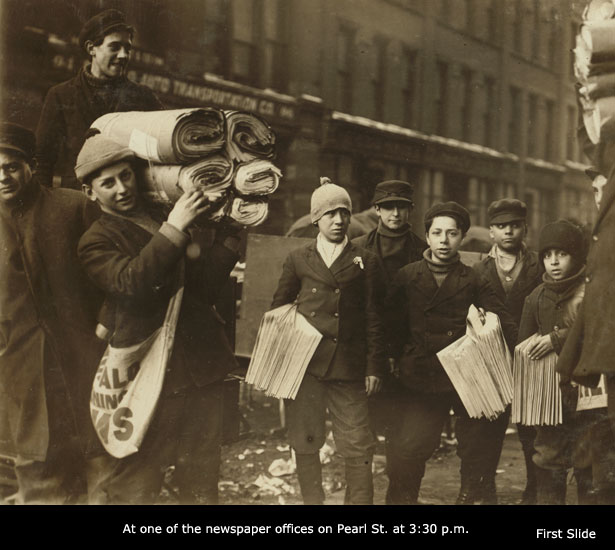

George Lewis, Buffalo newspaper distributor in 1890, with newsboys. Image source: TBHM

1898 Thanksgiving Dinner for newsboys at the 74th Regiment Armory, sponsored by the Ismailia Temple Mystic Shrine.

Over 1,000 boys were served 2,000 lbs. of turkey, 35 bushels of potatoes, 425 loaves of bread, 435 pies, and quantities of canned corn, apples, bananas, grapes. Image source: BECPL

New York State's legislature, like that of a number of other states, was struggling with creation of some regulation of what were called the "street trades," which encompassed child labor used for selling newspapers.

A committee of the University Settlement in New York City prepared the "Street Trades Bill" in 1903. It was written to include Buffalo, but strong opposition arose to that in the legislature. So Buffalo's Charity Organization Society was asked by supporters to make the city's case. Myron Adams, who was working at Buffalo's Welcome Hall, was tasked with preparing statistics. The result was a 12-page booklet, illustrated with these three photos, entitled "The Buffalo Newsboy and the Street Trades Bill." (available online)

Adams received help from his brother who was working in New York at the University Settlement. Together, they contacted local experts and spent two days interviewing 328 newsboys out of the approximately 700 Buffalo newsboys.

They found that 83% were under age 14 and 25% were under age 10. They estimated that there were approximately 150 boys under 10 selling papers. Of all 328, only 8 were orphans. The families of these boys were not destitute.

They found that 83% were under age 14 and 25% were under age 10. They estimated that there were approximately 150 boys under 10 selling papers. Of all 328, only 8 were orphans. The families of these boys were not destitute.

"Two boys, Joe R. and James R, aged six and eight years respectively, may be found at any time between 3:30 and 10:30 p.m. on Main Street near Mohawk. By their united efforts they are able to bring home fifty cents a day to support a mother and father with a numerous family, who compel them to do this work."

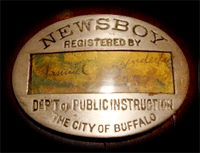

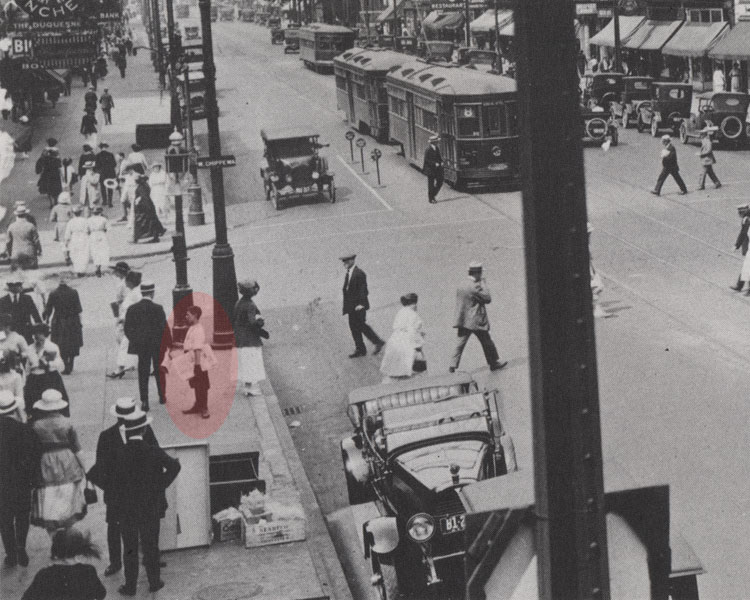

The Street Trades Bill became NYS law in 1903, and NY joined only Massachusetts and Wisconsin in having such a law. It required that newsboys be at least 10 years old (girls to be 16), have signed parental permission, be in good standing in school. If these conditions were met, the child would be issued a badge by the school (below). The children could sell papers only until 10 p.m. But enforcement provisions were diluted. Schools could issue the badge without actual proof of age and enforcement of the law was assigned to police. Supporters nevertheless called it a major victory.

The Street Trades Bill became NYS law in 1903, and NY joined only Massachusetts and Wisconsin in having such a law. It required that newsboys be at least 10 years old (girls to be 16), have signed parental permission, be in good standing in school. If these conditions were met, the child would be issued a badge by the school (below). The children could sell papers only until 10 p.m. But enforcement provisions were diluted. Schools could issue the badge without actual proof of age and enforcement of the law was assigned to police. Supporters nevertheless called it a major victory.

At left, two boys asleep in the cellar of a Buffalo newspaper office. "From ten to twenty boys of all ages sleep on the tables in this room until 3 a.m. when they go out to sell papers. The gunny-bag is drawn up to keep the boy's legs warm."

The booklet described the truancy of newsboys and their inability to adapt to the restrictions of regular employment after a career on the streets. And the State Industrial School in Rochester had 84 Buffalo boys incarcerated; 63 were newsboys. "At Father Baker's Protectory, in West Seneca, there has been expressed a desire to take as few newsboys as possible."

In 1904, the National Child Labor Committee was formed. One member, Lewis Hine, quit his career as a teacher to become an investigative photographer for the NCLC. Over a period of 5 years, Hine traveled the country taking more than 5,000 photos and slides to publicize the conditions of children laboring in industry. In February, 1910, during one of the coldest periods recorded in Buffalo, Hine photographed Buffalo newsboys at work. Despite the NYS law in force, Hine documented in these photos underage chilidren selling, children selling after 10 p.m. and children selling during school hours.

The photo slide show below contain Hine photos of Buffalo newsboys from the Library of Congress. Captions are from Hine's notes.

Newsboy at Main & Chippewa, 1920 Image source: Heritage Press

Newsboy at Main & Lafayette Square, 1920. Image source: Heritage Press.

The problem of "oppressive" child labor, as it was labeled, continued to be a struggle in state legislatures as well as in Congress, despite strong union support to limit employment of children in industry. The Supreme Court declared unconstitutional two federal laws passed in 1916 and 1933. A proposed Constitutional amendment passed in 1924 failed to receive enough ratifying votes. Finally, in the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, federal regulations still in force today detail what work children of various ages may perform.

In Buffalo, the Children's Aid Society and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children merged in 1916 and became Child and Family Services, which continues today.