The Many Lives of the King Complex, Rano Street, Buffalo

Part 2:Colonial Radio/Sylvania Radio & Television

The Colonial Radio Company moved into the capacious former King Radio Company complex in 1931. It employed 855 workers and sold radios under its own name as well as to Sears, Graybar Electric, Firestone, Goodyear, General Motors, Chrysler and Dunlop. Production in 1930 was 40,000 units; in 1934, 150,600 units. In 1940, with 1,762 employees, 631,000 radio receivers were produced in the Rano Street plant. Products included "midget" radios, console radios, combination radio-phonographs, and automobile radios.

1934 Colonial Radio manufactured under the Colonial name.

Image source: Radiola Guy

1934 Colonial Radio manufactured under the Colonial name.

Image source: Radiola Guy

Buffalo Evening News, March 14, 1940:

"Every minute at the plant of the Colonial Radio Corporation in Rano Street a new radio is produced for somebody's home or car. Production is at the rate of approximately 60 sets every hour. There are 3,000 separate parts and about 120 solder connections in every set.

"The production of radios appears to be an intricate business but Colonial has simplified the operations along its fast-moving production lines...Cold rolled steel is used for the mounting plates or frames for the basic chassis of Colonial radios. Die stamping machines cut the steel sheets and press them into various shapes. Small metal parts to hold the tubes, coils and other units are added to the frame so the basic chassis can be electro--plated in one operation...

From this point the frame and other parts, including coils, condensers, terminal boards, and a maze of circuit parts, many of which are purchased by the company from manufacturers of electrical supplies, move into the sub-assembly line. These partly assembled units are sent to the main assembly lines at points where they are to be added to the radios.

"There are from 16 to 21 nimble-fingered girl operators at each of the main assembly lines. Sitting at long tables each girl adds a few parts as the radios move forward. The first operator attaches the tube sockets to the mounting plate. Another adds condensers, a third the terminal board, others with little electric soldering irons join the wires. It requires but a few seconds for each operator to complete her task.

"After passing through the hands of the operators, the radio chassis is ready for tubing - placing the correct tube in each socket.

"Only a few minutes elapse from the time the basic chassis comes to the first girl on the main production line until every gadget is installed and every circuit completed so that the maze of wires becomes a sound producing instrument. At the end of the production line, the complete sets receive initial tests to check continuity of circuits.

"Others testers enclosed in electrostatically shielded booths to prevent stray signals or factory electrical interference from causing trouble, calibrate the radio dials so that stations are brought in at designated wave lengths...

"Approximately 50 different models are produced annually by Colonial The company normally employs 1400 workers, from 300 to 400 of whom have been with the company since it first started operation here."

Browse through models made at Rano Street below using the "back" and "next" controls.

Back Next

In 1940, Colonial acquired its first military contract. By 1942, it had dropped its production of civilian radio sets and devoted 100% of its production capacity to military products for World War II. Its first products were long range airborne transmitters, (TA-2, TA-6, TA-12), which were installed in British Lancaster and Halifax bombers. Next it produced radio sets (SCR-274, SCR-522) that were installed in every fighter, bomber, and trainer.

For the navy, Colonial produced walkie-talkie sets used aboard ship as emergency backup communications and also by the Marines in all of their Pacific engagements as well as the invasion of Italy. These 4-channel, battery-powered devices were portable yet complex and provided a much greater range than the type of walkie-talkie used by the Army.

Colonial engineers began research on an advanced radio set for aircraft in 1943; production of the AN/ARC-3 began in January, 1945. Solely produced by Colonial, this set had eight channels which could automatically be re-tuned in mid-air and soon became the standard equipment in all but the lightest military planes. It "permitted communication between all elements of a tactical air force, assignment of a channel to each element, and effective coordination between ground and air forces." (Buffalo Business, December 1945)

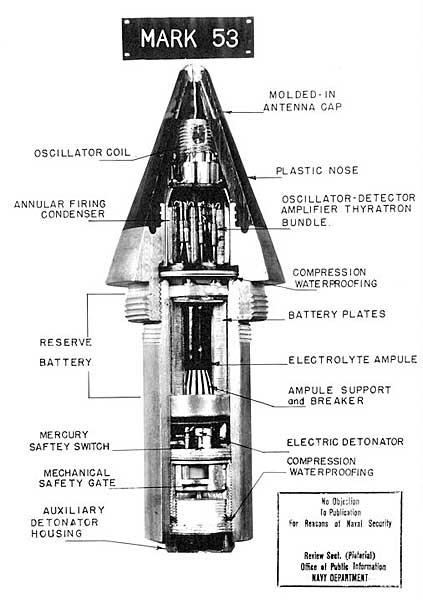

Diagram of the proximity fuse produced at the Colonial complex. Image source: Naval History & Heritage Command

During the last 14 months of World War II, 500 employees of Colonial were sworn to secrecy and assigned to work on a radio proximity fuse, a device affixed to anti-aircraft and field artillery shells that would automatically detonate the shell when it came within 70 feet of the target. This allowed the anti-aircraft shell to fatally disable an airplane without a direct hit, and the artillery shells had a more lethal effect on enemy ground troops than a more focused explosion. It succeeded in stopping Kamikaze raiders in the Pacific, stopped the buzz-bomb attacks over England during the summer of 1944, and turned back German General Van Runstedt's attack at the Battle of the Bulge.

The fuse consisted of four tiny vacuum tubes and circuitry that fit into a 5" anti-aircraft shell. A small battery, activated by the firing of the shell, provided the electrical power. When the shell was fired, the fuse sent out a continuous radar signal that determined when to detonate.

The device was so advanced that the military initially only allowed it to be used over water where a dud could not be retrieved and reverse-engineered by the enemy. It was finally approved for use over land in late 1944, just in time to assist at the Battle of the Bulge, when its designers persuaded the Joint Chiefs that the Germans could not successfully replicate the fuse before the war's end.

Historian James Phinney Baxter III concluded "If one looks at the proximity fuze program as a whole, the magnitude and complexity of the effort rank it among the three or four most extraordinary scientific achievements of the war."

In 1944, the Sylvania Electric Products Company purchased the Rano Street Colonial Radio complex. In 1948, the plant was re-organized and retooled for production of radios and the first television sets for Sears, Roebuck. In 1949, televisions were produced under the Slyvania label. The Rano Street plant was named headquarters of Slyvania's Radio and Television Division.

Click any to view larger image. Images source: Google

|

|

|

|

Sylvania's success in postwar America, with high demand for consumer products, was such that in 1953, the company constructed its largest television assembly plant in Batavia. Its new plant, modern and 422,000 square feet, left the 45 year-old Rano Street complex vacant. [The Batavia plant was shuttered in 1981 after Sylvania sold rights to the name "Sylvania" and "Philco" to Philips Electronics. Production had been shifting to Taiwan for a number of years.]

Sylvania, merging with GTE in 1959, would remain a large employer in Western New York for another 30 years, primarily through military contracts. In 1963, there were 700 employed at 175 Great Arrow in 208,000 square feet; 600 worked in laboratories at Wehrle and Cayuga in Amherst; 200 worked at 2777 Walden Avenue near Dick Road. Of the 1963 local college graduates, Sylvania hired 160. These locations benefitted from contracts from all branches of the military, from radios, walkie-talkies, navigation and instrumentation, microwave communications research, electronic countermeasures research, and ground control electronics for the Minuteman Intercontinental Ballistic Missile. By 1974, contracts for the Minuteman project alone had totaled $71 million dollars and requried 1,000 workers.

Bing view of the former King/Colonial/Sylvania complex.

Part of the King complex, showing the "KING" name on the smokestack.

The Rano Street complex, largely vacant in 2016 and partly damamged by a recent fire, remains.