Undated early photo of Grover Cleveland in Buffalo. Image source: New Jersey Dept of State.

Undated early photo of Grover Cleveland in Buffalo. Image source: New Jersey Dept of State.

Stephen Grover Cleveland spent 28 of his 71 years in Buffalo, stopping here at age 18 in what he had intended as a trip to Cleveland, Ohio. John Milburn, who had clerked for lawyer Cleveland decades earlier, wrote a memorial essay for the Buffalo Historical Society, claiming Cleveland as "true son" of Buffalo because he "developed and matured right here."

After his father, Richard Cleveland, died in 1853, 16 year-old Grover looked for ways to help support his widowed mother and younger siblings. After an unhappy year working at a school for the blind in New York City, he decided to travel to the city of Cleveland (named after his ancestor, Moses Cleveland, who came from England in 1635) to look for work. He stopped in Buffalo in May, 1855 to visit his uncle Lewis Allen and was persuaded to stay on and be paid to compile Allen's annual American Herd Book. A man of many accomplishments, Lewis Allen had a 500-acre farm on Grand Island on which he raised pedigreed Short-Horn and Devon cattle and Southdown sheep. Cleveland had a very pleasant time living at the Allen home in Black Rock and associating with his cousins He also found the fishing and game hunting on Grand Island to be excellent; these pasttimes would become lifelong.

When his year was up, Cleveland had decided to pursue a career in law. His uncle secured an appointment for him with the firm of Rogers & Bowen. Like so many others looking to learn the profession, he was handed a copy of Blackstone's text and instructed to read it. He said of his first day at the firm, "I was of so little consequence that they forgot my very existence, and after everybody had gone [to lunch], I found myself locked in. There was nothing for me to do but wait until somebody returned, and I remember that I went without any lunch that day."

In between his clerical duties, Cleveland taught himself from the text. Although he was regarded as a person of average intelligence, he was persistent in his efforts and, in May 1859 after three and a half years with Rogers & Bowen, was admitted to the bar. He remained with the firm as their chief clerk until 1863.

Buffalo was in many ways still a small town during the 1850s and 1860s. Grover Cleveland boarded on Oak Street in his early years as a lawyer and ate a local places that were half- saloon and half-restaurant. He favored the German places where he could enjoy lager, sausage and sauerkraut. He had a small group of close friends and like to play cards and sing along with a merry crowd at beer gardens.

saloon and half-restaurant. He favored the German places where he could enjoy lager, sausage and sauerkraut. He had a small group of close friends and like to play cards and sing along with a merry crowd at beer gardens.

c. 1864, aged 27, a big man with sandy hair and blue eyes. Image source: Library of Congress

One friend said of him: "He was not a great talker. Once in a while something would start him going, and he would run on for half an evening, but for the most part he let others do the talking; he listened." His voice was "a little higher than expected from such a large man...somewhat nasal, though not unpleasant [with] tenderness in it."

What Cleveland liked was hanging around John C. Level's livery stable at 24-26 Ellicott Street near Seneca. It was a hub of political gossip and Cleveland picked up sound advice on getting involved in local politics. He became a Democrat in spite of Level's Republican sentiments. He began working for the Democratic party as a foot soldier and became supervisor of Second Ward. That ward was populated by German Republicans, who voted for him despite his affiliation because they liked him personally; that ethnic group would continue to support him in his future political endeavors.

In 1863, he was appointed Assistant District Attorney for Erie County. The Civil War was underway and Cleveland had to decide to join the military or hire a substitute. Two of his brothers were Union officers and he was his widowed mother's sole support, so he hired George Brinski (or Beniski), a Buffalo Polish immigrant, for $300 ($5500 in 2012 dollars) to serve in his place.

28 Erie Street, built in 1856 by the law firm of Bowen & Rogers. Grover Cleveland, one year into his clerkship at the firm, helped move the furniture from the Spaulding Exchange into the new offices. (Painter Lars Sellstedt had a studio above the law offices.) Demolished 1920. Image source: World Port Celebration

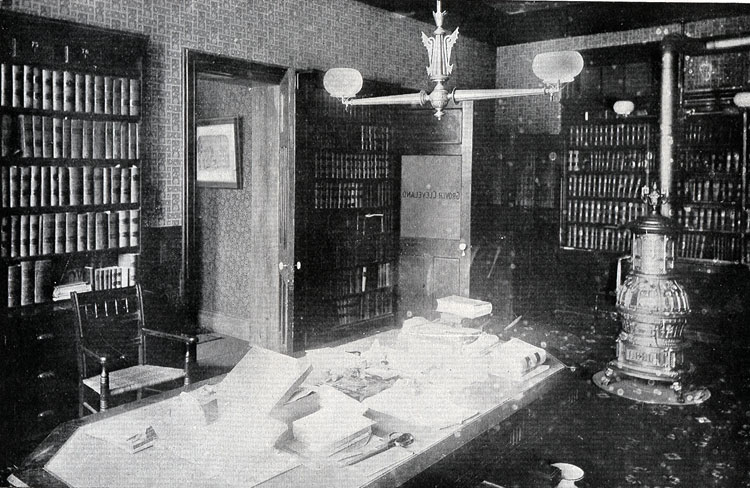

Cleveland's Law offices at the northwest corner of Main and Swan, the Weed block. Entrance was on the steps visible at left. The building was demolished in 1902. Building built by M & T Bank still stands. Image source: BECPL

Cleveland ran for District Attorney in 1865. He had been fulfilling that role since appointed as Assistant because the District Attorney, C.C. Torrance, lived in Gowanda and was in "delicate health." But he lost that election to Lyman Bass and decided to set up his own law practice. He joined with Isaac Vanderpoel and set up offices in the Weed block; he also lived in room F in the same building. Over the years between 1865 and 1882, his firm was known as Laning, Cleveland & Folsom; Bass, Cleveland & Bissell; Cleveland, Bissell & Sicard; Cleveland, Bissell, Sickard & Goodyear.

Among his best friends were Charles W. Miller, livery business owner and law partner Oscar Folsom, described as a "gay, brilliant sportsman." These and around 20 other friends formed the Beaver Club on Grand Island with a clubhouse on Beaver Island. Cleveland remained its president for its existence. The members enjoyed fishing and duck hunting and socializing at their club. Oscar Folsom, who had married in 1863 and was father to Frances "Frank" Folsom, used to bring his wife and little daughter to outings at the clubhouse. He was killed on his way home from Beaver Club in 1875 when his carriage crashed.

Grover Cleveland's law office as it appeared in 1882 when he was elected mayor. Former President Millard Fillmore had an office adjacent to Cleveland's in the Weed block.

Image source: Picture Book of Earlier Buffalo.

Cleveland assumed responsbility for Folsom's widow and daughter. He had been in their lives from the beginning, having purchased the first baby carriage for little Frank. She called him "Uncle Cleve." The year before Folsom's death, Cleveland had assumed paternal responsibility for a child born out of wedlock to Maria Halpin, a Buffalo widow and head of the cloak department at Flint and Kent. Mrs. Halpin had been entertaining a number of married men, including Oscar Folsom. She also entertained Grover Cleveland, bachelor. When she gave birth to a son, Mrs. Halpin named him "Oscar Folsom Cleveland." She named Cleveland as father, though he and other friends doubted its accuracy and thought she was looking for Cleveland to marry her. His focus instead was on protecting his close friend from scandal and so he paid to support the child. This would not be the end of the story, however, as Mrs. Halpin would lose custody of the child who was placed in an orphanage for a time. And, when he ran for President in 1884, opponents raised the question of his illegitimate child to cast doubt on his character. He never forgot or forgave the two Buffalo ministers or the newspaper for spreading stories about him that accused him of low morals..

Cleveland and his partners built a large practice and he became highly respected by his peers, who particularly liked to have him serve as referee because, as Frank M. Loomis said, "they knew his decisions would be founded on law."

Cleveland during his mayoral term. Image source: History of the Niagara Frontier (Merton Wilner)

Cleveland during his mayoral term. Image source: History of the Niagara Frontier (Merton Wilner)

His best friend, Wilson Bissell, spoke of how he over-prepared for a case that had to go to court. "Once pushed or dragged into court by his client, he was not only part and parcel of the case, but bold and self-reliant; and through much practise he acquired great skills and sagacity in marshalling his facts before a jury."

Grover Cleveland's lack of desire to amass a wealthy list of clients or actively seek higher elective office marked his years as a practicing attorney. In 1871, he accepted the nomination for sheriff of Erie County and was elected by a very small margin. Despite spending a good percentage of his time in recreational activities, Cleveland nonetheless became noticed for his pursuit of corruption in form of bribes and illegal profits from contracts within the sheriff's organization. This reputation led to his nomination in 1881 for mayor of Buffalo. So ready for reform were Buffalo voters that the Republican party split over the chosen candidate, Milton C. Beebe. Only one newspaper opposed Cleveland.

In one campaign speech, he remarked, "It is a good thing for the people now and then to rise up and let the office holders know that they are responsible to the masses."

He was elected as the antithesis of the typical Buffalo political machine politician by a populace who saw high taxes, expensive police and fire departments, and poor services. Cleveland spent his short tenure as mayor fighting with the Common Council and vetoing legislation at the rate of one to three vetoes per week; he became known as the "Veto Mayor.". The most legendary of his successes in reducing corruption came over the awarding of a contract for street cleaning.

His reputation reached Albany where a gubernatorial race was coming. Both the Republican and Democratice parties were divided in 1882. The same kind of corruption that Cleveland struggled against in Buffalo was also raging in state government.

Cleveland as Governor. Image source: NY Dept of State

Riding on his reputation and the slogan that he had adopted when running for mayor, "Public office is a public trust," Grover Cleveland became Governor of New York in 1882, one year after being elected mayor of Buffalo. He was 46 years old, still a bachelor. His election was attributed to "Cleveland Luck," being the right person at the right time in the right place.

Cleveland's Albany habits mirrored those of his career as a lawyer; after a full day at the capitol, he usually worked until 11 p.m. in the office he had installed in the governor's mansion. The Albany Evening Journal said, "Plainly, he is a man who is not taking enough exercise; he remains within doors constantly, eats and works, eats and works, and works and eats...There is not a night last week that he departed from the new capitol before one a.m. Such work is killing work."

In 1883, Cleveland came to Buffalo to make an address and was invited to a picnic at the Pine Ridge Road estate of George Urban, Jr. Though Urban was a Republican, he and Cleveland were longtime friends. It was there that Gerhard Lang raised a glass and toasted, "Here's to Grover Cleveland, our next president." Of the forty people there, only Cleveland was surprised.

Two years later, in November, 1884, his "Cleveland Luck" would again be invoked when Grover Cleveland was elected President of the United States. The speed with which his career traveled from Buffalo lawyer to Washington, D.C. in three years led John Milburn to summarize it as "a tale out of wonderland."

Buffalo would continue to love Grover Cleveland, calling him one of its own, proud of having sent a second President to Washington, but Cleveland did not return the love. He was deeply hurt by the mud-slinging over the illegitimate child that he had long before publicly claimed as his own. And then, when he became President, he was appalled by the friends from Buffalo who relentlessly clamoured to be awarded offices, when it was well-known that he was against patronage. He nearly broke permanently with his best friend, Wilson Bissell, who was thought to be a sure thing for a cabinet post. He said, "I shall not come to Buffalo...as I feel at this moment I would never go there again if I could avoid it."

When he married Buffalonian Frances Folsom, it took place at the White House in Washington. The years between Cleveland's Presidential terms were spent in New York City, where Cleveland practiced law. And when he completed his second term of office, the Clevelands retired to Princeton, New Jersey, in the state where he had been born.

He did visit Buffalo again, however, in 1903, when he attended the funeral of Wilson Bissell. And, in his latter years, Grover Cleveland spoke fondly of his Buffalo friends and the memories they shared.

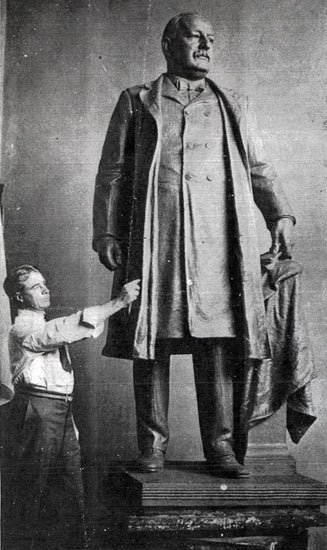

Sculptor Bryant Baker poses beside his model of Grover Cleveland in 1930. It was the first statue of the former President to be created and was installed outside City Hall in July, 1932. Image source: BECPL

Buffalo today is plentiful with buildings named after Cleveland and other reminders, including a statue on the north side of Buffalo City Hall, installed in 1932 during the city's centennial. A plaque on the wall of 290 Main St. remembers his office in the Weed block.