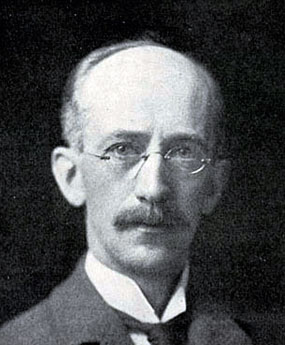

John J. Albright (black and white image of portrait owned by Albright-Knox).

John J. Albright (black and white image of portrait owned by Albright-Knox).

Image source: "100: The Buffalo Fine Arts Academy"

"As a lover of art and a believer in its beneficient influence in such a city as ours I have long felt that the Academy could not fulfill the purpose of its founders and friends without the possession of a permanent and suitable home...From such inquiries as I have been able to make I am led to believe that a suitable building would cost from $300,000 to $350,000. This expenditure I am ready to meet..."

After John J. Albright, a curator (director) of the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, presented this letter to the board on January 15, 1900, the room was silent for a full minute. Then 81-year old Lars Sellsted, who had organized the first art exhibition in Buffalo in 1862, "broke down and crossing to Mr. Albright, clasped his hand." After five different borrowed or rented locations in 38 years, the Academy would have a home.*

And not just any home. Albright specified that the art gallery be constructed of white marble and be located in Delaware Park away from all potential industrial activity that would mar its beauty.

Albright, then 52 years old, would eventually spend $1,000,000 dollars ($28 million in today's dollars) on the gallery that even before it was completed was called the Albright Art Gallery.

He optimistically suggested that, if completed in time for the Pan-American Exposition the next year, it could be used for the Exposition's art gallery. (It was not.)

Floor plan where someone wrote "art school" across galleries 16, 17, and 18. Image source: "Academy Notes, 1905."

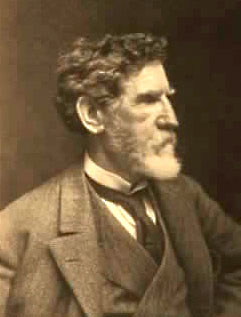

E.B. Green, 1899. Image source: Pan-American Herald.

E.B. Green, 1899. Image source: Pan-American Herald.

Albright called on E.B. Green, who by 1900 had become his first choice for all his personal, business and philanthropic constructions. Green had designed the Buffalo Bolt Company forge and finishing shops (owned by Albright and Edmund Hayes) in North Tonawanda (1894); Welcome Hall and Cottage (1897); his family compound at 733 West Ferry. Green traveled the U.S. after being retained for the design of the new art gallery, evaluating the best aspects of other galleries. He wanted to place the building on its park site so that its attractiveness was emphasized. And, "it should be so impressive in its dignity that men should approach it with a certain feeling of reverence; with a feeling calculated to intensify the appreciation of responsibility and duty as citizens having personal participatory interest in the structure and contents." (Cornelia Bentley Sage, 1905). Green chose to design the gallery along the lines of a Greek temple. He specified 102 columns, more than any other American structure except the Capitol Building in Washington.

As important to Green was the practical consideration of the interior spaces. Green designed the rooms to be well-proportioned with walls not too high. Three large spaces were lighted by double glass skylights with electrical lighting concealed between the layers of glass. The arrangement of rooms was designed to permit free flow of visitors without congestion. A grand staircase was purposely left out of the design because it detracted from this.

Placing a column, 1901. Image source: TBHM

The building was constructed using 5,000 tons of white marble from a Maryland quarry, the same marble used in the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C. This increased the costs considerably and, between securing materials and some labor troubles, the construction of the gallery lasted several years. E.B. Green felt it necessary to respond to critics about the lengthy construction in April, 1901: "Architectural works of art cannot be reared in a hurry. It takes time and care. Some of the Pan-American officials have said we could finish the gallery, if we tried, before the Exposition was dedicated. If it were a ten-story merchantile building, perhaps we might. They do not understand what it means to build a beautiful marble structure like the gallery. Take, for instance, those immense marble columns with which the gallery is to be adorned... We have been waiting a long time for the last column. It has just been secured, and they started two gangs of thirty men at work on it. They work two shifts of cutters eight hours each, and during the remaining eight hours of the day, another gang polishes what they have finished, so they are working every minute of the day and night on that one column and yet it will take them thirty days to finish it. There is another thing very few people know. One man sets all the marble that goes into the gallery...from the smallest block to the great columns. Of course he has about a dozen men helping him as laborers and seven or eight derricks and an engine, but when a piece of marble goes into place he puts it there. It is his eye alone that determines its fitness. When the gallery is finished, the master touch of one single hand will be stamped over it." ( He did not reveal the name of that man.)

East side construction view showing temporary plaster caryatids. Image source: "100: The Buffalo Fine Arts Academy"

The gallery opened to majestic ceremonies on May 31, 1905. Dignitaries who spoke included Harvard President, Charles William Eliot, who gave the key address. Four city choral organizations performed together; a poem written celebrating the gallery's opening was read by its author, Richard Watson Gilder. The one person whose photograph did not appear anywhere was the benefactor. Nor did John J. Albright speak to the assembled. It was his lifetime preference to be away from the spotlight. His grandson, Birge Albright, said that Albright took his friends to the gallery on Sundays when there were few others around.

One of the two skylighted galleries. Image source: Library of Congress

The visitors, both invited guests and the general public, who streamed into the Albright Art Gallery at its opening saw paintings on loan from galleries across the U.S. and Canada. These included Manet, Rembrandt, Velasquez, Delacroix, as well as Millais, Whistler, and the original plaster model for the Shaw Memorial (Boston Common) by Augustus St. Gaudens.

Sculpture court with plaster casts of classical statuary. Image source: Library of Congress

East view of the gallery with the "porches" missing, awaiting future caryatids, 1911. Image source: Library of Congress

Augustus St. Gaudens, 1905.

Augustus St. Gaudens, 1905.

Image source: Wikipedia

Two reproductions of the "porch of the maidens" from the Erectheum temple on the Acropolis in Athens, Greece, were always intended to be created for the east side of the gallery. Albright had met St. Gaudens, likely during his visit to the Pan-American Exposition in 1901, and commissioned him to create caryatids for the Albright Art Gallery. They corresponded regarding the number and design of the women; St. Gaudens eventually determined that he wanted to stay close to the ancient design and style. But, he confessed, "This doing something to recall the Erectheum is what perhaps frightens me more than anything I have done in my life. It seems presumptuous." But he persevered and had plaster models completed when he died in 1907 at age 59. Assistants carved the final versions in light gray marble; each is eight feet tall and weighs three tons. There are four different statues, duplicated, representing Victory, Music, Painting, Sculpture.

Unfortunately, disagreements between the St. Gaudens estate and Albright delayed their transfer of the statues which cost Albright $100,000 - 115,000. Eventually they were delivered to Buffalo; one group of four was installed on a wooden platform of the south wing temporarily. It remained there for 25 years. The other four statues were stored in the basement of the gallery.

Detail of the "Music" caryatid at the Art Gallery.

Why were they not installed? John J. Albright had spent and lent his fortune over the years and was hoping to generate sufficient new income to afford the masonry constructions to create the "porch of the maidens." Unfortunately, he died in August, 1931, never having formally given the statues to the gallery or city. His family, hoping to recoup some of the cost, offered the statues for sale for $50,000. Out of town inquiries began to come in. It was feared that they would be dispersed and Albright's plans turned to dust. But two years later, the family's trustees accepted an offer by the city of $25,000, a sum cobbled together during the Depression from funds left by the late Hamilton Ward and James G. Forsyth. Installation costs were covered by Federal Work Relief Funds.

East view of the Albright-Knox, caryatids in place.

*The New York Times responded to this announcement on February 3, 1900: "At last Buffalo is to be congratulated on a visible progress in culture. Blessings, like misfortunes, rarely come singly, and after years and years of waiting, in a sordid devotion to affairs of commerce and industry that had attracted attention by its single-heartedness, Buffalo takes a sudden and long leap forward in visible civic fruits of culture."

To read about the decisions made in the late 1950's to expand the gallery, look here.