Influenza on the Homefront (Part 1)

The influenza pandemic that swept the world in 1918 started in the American midwest before accompanying troops to Europe. It would eventually kill over 500,000 Americans and more than 50 million people around the world. Wherever it spread, it targeted healthy individuals of all ages, especially the young men and women whose age precluded immunity from past flu seasons. And it spread with astonishing speed, overwhelming homefront medical personnel and facilities at the time when most doctors and many nurses had been mobilized for the war effort and sent to Europe. It inspired a great deal of misinformation and prompted marketers to target frightened individuals with advertisements and commentary that emptied their wallets needlessly. How did the story unfold in Western New York?

Buffalo area newspaper reports began printing stories from New York City in mid-August, 1918. One story repeated the advice of the New York City health department that people should avoid kissing or, if they must, to do so "through a handkerchief." That city was agitated when a ship was allowed to land and its passengers permitted to disembark despite knowledge by local officials that some passengers had died of what was then called "The Spanish Flu." But the real worry for local parents was the news on August 16 that American soldiers abroad were required to gargle each morning to "cleanse their throats with an antiseptic solution" as an influenza preventative. Western New York parents wondered if their sons were ill with what was being called "the prevalent wave of influenza."

On August 22, a syndicated columnist named "Dr. W. A.Evans" titled his essay in the Buffalo Commercial, "Spanish Influenza on the Way!" He suggested that the old and infirm "will do well to plan to winter in Southern California, Florida, the Mississipi coast or the southwest." He also advised good ventilation, noting that there was no help for the flu but bed rest.

Why was it called "Spanish Influenza"? Spain, neutral in WW1, had no press censorship and so first reports of influenza appeared in the Spanish press. Wartime censorship prevented the news from appearing elsewher in Europe and so the illness was appended with "Spanish."

September 1918

Acting Buffalo Health Commissioner Dr. Franklin C. Gram announced on September 21 that there were no cases of influenza in Buffalo. That same day newspapers featured a story about 300 Polish soldiers ill with influenza while training at Niagara-on-the-Lake. Polish immigrants were especially vulnerable to influenza because they had emigrated from rural areas in Poland with no prior exposure to these contagious diseases. (Twenty-five of the forty-one Polish soldiers who died of influenza are buried at Niagara-on-the-Lake. Look here for photos of that cemetery.) How long until the flu spread across the Niagara River?

The Courier and Buffalo Evening News printed stories that were hardly reassuring. Boston, Massachusetts had 70 deaths in a twenty-four period. Influenza was epidemic in Camp Devens, MA, Camp Upton, NY and Camp Lee, VA in addition to Camp Gordon, GA, Camp Syracuse, NY, Camp Humphreys, VA, Camp Merrit, NJ, and Camp Lewis, WA. On September 20, the American Surgeon General noted that "a fatal outcome was not uncommon" and said that the infection takes the form of pneumonia.(The wave of influenza that struck in the summer and fall of 1918 rapidly developed what is now called ARDS, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome; it remains today a life-threatening condition, requiring the use of ventilators which did not exist in 1918.) Still the draftees from around the country were forwarded to camps for training. On September 24, influenza was found in 25 training camps.

But the grim news was much closer to home. The third week in September, Louis Edward Wolff, a radio service operator,of 977 MIchigan Avenue, died at the Great Lakes Training Center in Illinois. Thirty-one years old, he was survived by his mother, four brothers and a sister.

The bad news began coming in greater numbers with photos of the dead from the Great Lakes Center. At left was Frank L. Miano 24, who lived on 493 7th Street and was secretary/treasurer of the Newsboys' Association. For years he worked the newstand at Main and Mohawk Streets. He fell ill just after returning from leave in Buffalo.

At right is the photo of 26 year-old Wilfred H. Hopper who died three days after falling ill with influenza. He was the only son of Mrs. Anna Hopper, 246 Barton Street.

Orlo B. Adolf of Bowmansville also died at Great Lakes.. He graduated from Depew High School and worked for the C.B. Hodges & Co. hardware dealers. HIs funeral was held at the family home.

Dr. Gram announced on September 25 that three supposed cases of Spanish influenza in the city were "ordinary grippe." He could not know that definitively because there were no laboratory tests to differentiate. And, most importantly, the existence of viruses, which cause influenza, was unknown at that time and would be for another 15 years.

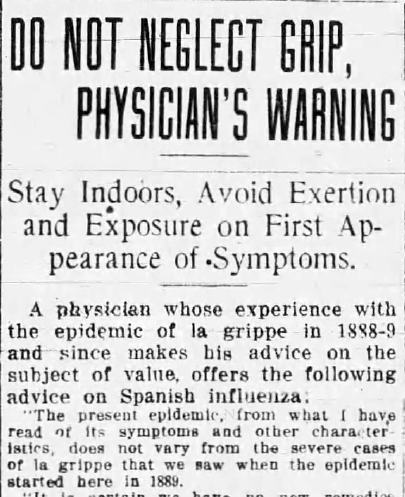

A Buffalo physician with past experience with influenza outbreaks said on September 28: "If Buffalo is attacked by this epidemic as severely as reported from some of the eastern cities, it will be difficult for the medical profession, with its numbers depleted as they are by the call to the colors, to take care of those that ought to have their attention. The NEWS can do an immense service to the community by publishing timely and sound advice upon the subject, which most any physician will be glad to furnish."

A Buffalo physician with past experience with influenza outbreaks said on September 28: "If Buffalo is attacked by this epidemic as severely as reported from some of the eastern cities, it will be difficult for the medical profession, with its numbers depleted as they are by the call to the colors, to take care of those that ought to have their attention. The NEWS can do an immense service to the community by publishing timely and sound advice upon the subject, which most any physician will be glad to furnish."

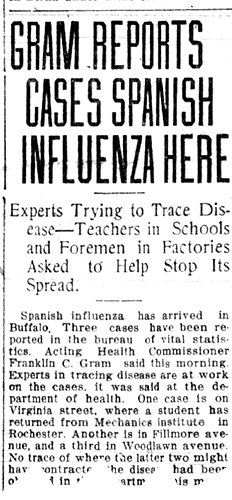

The headline at left is what readers of the Buffalo Evening News saw on September 23, 1918. One patient had returned from Rochester, but the other two were local and no known source was evident. He recommended that doctors prescribe a spray of sulphate of zinc as a curative and preventative. Dr. Gram described the symptoms of the influenza as starting with a chill, "considerable prostration, headache, general malaise and pains, the temperature may rise to 105 degrees, and the duration is usually four or five days..."

People were warned to be alert to persons coughing or sneezing. The article ended with a line indicating that he had written to the United States Public Health service for the latest information on the disease. He also requested that teachers and physicians notify his office of persons with symptoms so that his office could determine the extent of the spread of influenza locally.

To add to the confusion, Dr. Gram said on September 24 in the Buffalo Express newspaper that "investigation [had] shown three supposed cases of Spanish influenza in this city" were in fact "ordinary grippe."

Part of this misinformation was caused by the aforementioned lack of medical knowledge of the time, but there was another, more tragic, reason for medical professionals in the United States to downplay the spread of influenza. The U.S. government had passed a sweeping law in 1917 called the Espionage Act, which made it a federal offense to promote any ideas that would demoralize or be disloyal. Newspapers were compliant with this repression and officials like Dr. Gram contributed to the disinformation. The false reassurances from public officials contributed to distrust and to the delay of action to stem the spread of influenza in Western New York and around the country. (Historians have discovered that all localities addressed influenza the same way. First, they told the public not to worry, that public health officials would keep them safe. Second, when cases first emerged, officials reassured the public that it was just ordinary influenza, 'grippe'. Third, when it was engulfing the community, they repeated that the worst was over. These statements served to give the public a deep sense that they were not being told the truth.)

September 28 brought news of Buffalo soldiers who had been killed, wounded, or missing in action during the big offensive action against the Germans. The same article reported that Roscoe Vaugh had died in Camp Jackson, SC, after a 4-day illness that was unnamed, but certainly influenza. He had left Buffalo only three weeks earlier for training. Twenty-one years old, he would not be returning to his job at the Pierce-Arrow factory or his work with the YMCA.

The first of a series of advertisements in the Buffalo papers promoting products that claimed to prevent or cure influenza.

The first of a series of advertisements in the Buffalo papers promoting products that claimed to prevent or cure influenza.

Things in Buffalo were about to get worse very quickly.