The Metcalfe House's Last Days: 125 North Street

The front of the Metcalfe House before 1900. Image source: TBHM

The story began simply. In 1882, Mrs. Erzelia Metcalfe, widow of banker and businessman James H. Metcalfe, hired a young firm from New York City, McKim, Mead & White, to design the company's first Buffalo residence. The design she settled upon was a "suburban house," a new style being tried. It suited people who did not want enormous mansions; its ceilings were 9 feet tall, its rooms smaller and more intimate; fewer servants were needed. The Buffalo Metcalfe House suited Mrs. Metcalfe and her son, James, the only one of her four children to reside there. But it had made an impression in national magazines, such as Artistic Country Seats, 1887, as something special.

The Metcalfe House as seen from Delaware Avenue (Williams-Butler mansion at right). Image source: Library of Congress

The house was sold in 1905 to Edwin Thomas. It seems that it was he who made the first of several alterations to the original design. He extended the front piazza across the entire front of the house, and made other exterior alterations. Then, beginning in 1921, the house became a boarding house and remained used for that until the late 1970s, when it was sold to Sportsystems.

Side view of the Metcalfe House, seen from the Williams-Butler property.

Image source: Triumvirate McKim, Mead & White, Mosette Broderick

Sportsystems Corporation purchased the Metcalfe House before buying the adjacent Butler mansion. From the beginning, the corporation intended to create parking for the Butler mansion, whose many large rooms would convert very easily to offices for its 80 employees. To create the parking spaces for the employees, the Metcalfe House would have to be removed. There was precedent for this action on North Street. The adjacent property at 127 North and the Edmund Hayes mansion next to that at 147 North, had both been demolished by this time and were serving as parking lots. With demolition of the Metcalfe House, there would be a continuous expanse of parking on North street.

The house, viewed from North Street, 1979-80. Photo courtesy Michael and Jerome Puma.

The headline in the Courier-Express on December 9, 1977, was a small one, on page 18 of Section C: "Metcalfe House Demolition In Sportsystems Office Plan." The corporation filed its plans with the Buffalo Landmark and Preservation Board, created in 1977. The corporation said, "The demolition of the house and rear building on the site is required to enhance and augment the entire setting for a restored Butler Mansion and provide necessary parking - not otherwise available in the area - for executive personnel who will have offices at Bufler mansion. Moreover, the present poor condition of the buildings on the site and the indiscriminate inside and outside additions to the house which have no architectural merit, recommend, if not require, demolition..." The plan went to add that this demolition and the restoration of the Butler mansion would "foster civic pride, improve property values in the area, furnish support and stimulus to the community, and encourage the adaptive reuse of historic buildings having architectural value for business and institutional purposes."

There was an immediate response to the plans from community preservationists like Austin Fox, president of the Landmark Society of the Niagara Frontier. He said, "I feel the Metcalfe House is a very important part of the architectural heritage of Buffalo... I think it would be a sad thing to demolish the Metcalfe House before every other possibility of alternate parking has been researched to the fullest extent possible."

The chair of the Buffalo Landmark and Preservation Board, Olaf Shelgren, had no public comment. But a Board member, Appleton "Tony" Fryer, whose aunt had owned the Metcalfe House during some of its boarding house years, made widely quoted remarks about the Metcalfe House. "As preservationists, you don't just save things because they are old. That building has been a disgrace since 1921."

If the Landmark and Preservation Board voted to disapprove the plans, the only effect would be to delay demolition for 180 days.

1979-80. Photo courtesy Michael and Jerome Puma.

New York State officials warned that an application to create the Allentown Historic District might be in jeopardy if the Metcalfe House were demolished because it was contained within the proposed boundaries. By December 18, with criticism rising against the demolition, Sportsystems stated clearly that without parking, the corporation could not use the Butler Mansion for its headquarters. It defended its position against any adaptive reuse for the Metcalfe House by saying that it offered only cramped spaces upstairs and declaring that the four major rooms downstairs had "lost their original charm due to earlier remodeling." It added that the only practical way to save historic aspects of the house would be to remove wooden paneling, mooldings and other fixtures and reconstruct them elsewhere.

1980. Photo courtesy Michael and Jerome Puma.

That was exactly what Dr. Frank Kowsky, chair of the Fine Arts Department at SUNY College at Buffalo, had in mind. By coincidence, he was hosting R. Craig Miller, Assistant Curator of the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum, in Buffalo for a lecture. Kowsky and Miller contacted the contractor for the planned demolition and gained entry to the house. Miller immediately expressed an interest in the stair hall and entrance and parlor. Kowsky also had in mind saving the dining room and library and went to work persuading his dean and Buffalo State president, Bruce Johnstone, to agree.

Kowsky said that Sportsystems "has a masterpiece on their hands, (comparable) to finding a Rembrandt in the attic."

The National Trust for Historic Preservation's Northeast Region wrote in support for the conservation of the building. Its demolition would be "a clear loss to the integrity of the street, especially since three examples by McKim, Mead and White exist in the area."

1980. Photo courtesy Michael and Jerome Puma.

On December 19, 1979, the Buffalo Landmark and Preservation Board approved the demolition plan for the Metcalfe House after Sportsystems agreed to finance preservation of portions of the building's interior. The corporation also agreed to hold off demolition until February 1. As for the application for the Historic Allentown District, Board president Olaf Shelgren said there would be no problem because the boundaries of the proposed district would be adjusted to eliminate the northern half of North Street, the side where the Metcalfe House was located.

On January 17, 1980, five members of the Buffalo Common Council toured the Metcalfe House. If it chose, the Council could overrule the Buffalo Landmark and Preservation Board, but that would only result in delaying demolition until June. One of the Council members, Eugene Fahey, said that the demolition was "for convenient parking. My inclinations are not to trade a building for a parking lot." He made a resolution to hold a public hearing on the issue with the Board and Sportsystems. Nothing came of this.

Courier-Express art critic, Richard Huntington, said in a lengthy feature on January 27, 1980, "It can be said flatly that this is not a house which can be experienced piecemeal. A room in limbo behind velvet ropes or an architectural fragment in a glass case cannot possibly convey the joyous interaction of White's inventions. The Metcalfe interior is an active dialogue with many varied voices, never a monologue."

An architecture student, Mark J. O'Connor, filed a suit on February 8, on behalf of "Save the Artistic Metcalfe House Association." Part of the lawsuit was to delay stripping of the interior for shipment out of the city to the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Legal arguments were rejected by the State Supreme Court the next day.

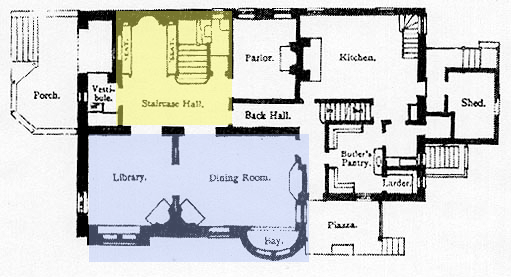

First Floor Plan of the Metcalf House; coloring shows the portions saved. Image source: The Little Journal, 1980

To view re-created rooms from the Metcalfe House, click on the yellow box to see the Staircase Hall;

click on the blue box to see the Library/Dining rooms.

It took two weeks to dismantle the interior. Parts were sent to the Metropolitan; it would be eleven years before the entry and stairhall went on exhibit in the American Wing in 1991. The next year, Peter M. Kenny, came to Buffalo from the The Met to give a lecture and came away with two windows that had been moved from their original location in later remodeling. One had originally been saved by John Conlin and the other donated to Austin Fox for the Met by John Lenahan. They were installed in their original locations in the inglenook of the stairhall. The Met had also received the parlor in 1980 but difficulties in identifying the original design have left it in storage. Other parts were delivered to Buffalo State, which unveiled the Metcalfe rooms in Rockwell Hall with little fanfare in 1989.

The house was demolished and the company then decided that the parking was not needed, after all. Instead, gardens were laid out on part of the site, which remain in 2013. Subsequently, Mosette Broderick, a national McKim, Mead & White expert, said emphatically that the Metcalfe House was the building to save instead of the Butler Mansion.

But the Metcalfe House demolition had ignited a fire in some Western New Yorkers. They saw the ineffective Buffalo Landmark and Preservation Board and the mild mannered Landmark Society of the Niagara Frontier and wanted a more activist approach to historical preservation. So many buildings had already been lost that the further loss of the Metcalfe House created the desire to confront public and private interests over the future of Buffalo's architectural heritage. And so, in 1981 the Preservation Coalition of Erie County was founded by Peter Filim, Susan McCartney, Joan Bozer, Scott Field, Kitty Turgeon and Robert Rust. Over the next 27 years, the Coalition helped establish three historic districts in Buffalo, took title to the Central Terminal and spun it off to the Central Terminal Corporation, sued New York State to preserve the Canal district, sued New York State to force stabilization of the Richardson Complex, among other preservation achievements.

The legacy of the Metcalfe House in 2013 lies in the fact that some of its extraordinary interior is preserved for future generations to study and appreciate in the two cities that were home to the Metcalfes. And the grass-roots preservation movement inspired after the demolition merged in 2008 with the Landmark Society of the Niagara Frontier to form Preservation Buffalo Niagara, a growing and engaged organization taking a leadership role in saving and promoting the architectural legacy of Western New York.

The former site of the Metcalfe House in 2013.

I extend very special thanks to Michael and Jerome Puma for permission to use photos taken by Jerome Puma in 1980. Thanks also to Susan Kendt and Denise Zenicki of the Dean's Office, Arts and Humanities, SUNY College at Buffalo. And thank you to John Conlin for sharing history of the preservation movement in Buffalo in 1980.

To read the text of Dr. Frank Kowsky's article from the 1980 Little Journal on the Metcalfe House, look here.