Harriet Townsend and the Women's Union

The city of Buffalo, after the Civil War, experienced growing influxes of population seeking work at the many new industries on the Niagara Frontier. The city's lack of housing and substandard schools created social conditions that left legions of women and their children in poverty that was unrelieved by the small efforts of the Buffalo Association for the Relief of the Poor. Even the Charity Organization Society could do nothing to ensure steady year-round employment for factory workers so that they could secure a better standard of living for themselves. In 1884, the Literary Club of the Church of the Messiah, a Universalist Church on Main Street, invited Abby Morton Diaz, founder of the Women's Educational and Industrial Union in Boston, to speak at the Fitch Creche on Swan Street. The event was sponsored by the Charity Organization Society. Within two weeks, the second Women's Union in the country was established in Buffalo, with Harriet Townsend as president. Harriet Townsend was 45 when the Women's Union was founded in 1884. She was the driving force behind the establishment of the organization with her exceptional intelligence, vision and the managerial qualities of a CEO. Daughter of Benjamin Hale Austin, prominent Buffalo lawyer, she was raised in the Universalist Church and educated at the Buffalo Seminary. Her father encouraged her to be informed on the issues of the day. In 1861, she married Geroge Townsend, partner in Clarke, Townsend & Company, grain merchants associated with the Niagara elevator. They had no children, which freed her to work full-time for women's advancement. |

She advocated for women’s rights all of her adult life. She counted among her friends Abby Morton Diaz, founder of the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union of Boston, Susan B. Anthony, Frances Willard, Julia Ward Howe. "Hattie" Townsend was the founder and president for 24 years of the Women's Literary Club of the Universalist Church of the Messiah in 1880, one of the first purely literary groups in the city. There was so much interest that membership quickly grew to 150. The club wrote of itself: "Although its avowed purpose is mental development, the club stands ready to aid in any movement for the elevation of womanhood." That that was what Harriet Townsend was about. She attended the first convention of Women's Clubs in New York; the Literary Club was a charter member of both the State and National Federation of Women's Clubs, and she served on the board of directors for the General Federation. She was associated with the Association for the Advancement of Women, a national association promoting opportunities for women. Townsend was fond of quoting great thinkers from the past. She used this quote from Aristotle in an annual report to the Union membership: "We live in deeds, not years: In thoughts not breaths; In feelings, not in figures on a dial. We should count time by heart throbs. He most lives Who thinks most, feels the noblest, acts the best.” She published four books on Emerson, Dickens, Thoreau, and "Reminiscences of Famous Women" as Union fundraisers, gave numerous papers at state and national conferences, and wrote articles for magazines. |

The Union purchased the Babcock Home in 1886 for $18,000, raising $12,000 in six weeks for a down payment. The organizers of the Women's Educational and Industrial Union declared that their organization was intended to "provide a common meeting place for women, with an atmosphere so cordial that none should be out of place, where the rich woman should forget her riches, the poor woman her poverty; to freely give the advantages women need -- graces of heart, culture of the intellect, employment for the hand and brain, a more exalted opinion of home life, protection from the oppressor, access to good literature, and to offer a welcome and sympathy to all who should cross its threshold." Its motto was, "Each for all and all for each." Membership was $1.00.

Harriet Townsend said in the 1888 annual report to the Union membership: "We no longer listen to the selfish moralist who cries, 'Let the woman stay in her home, her only safe haven.'" In 1896, she said of the Union, "it is not, we repeat, an association of benevolent, well-to-do women, joined for the purpose of reaching down to help the poor and persecuted women, but a Union of all classes and conditions of women." The concept was unique in American history and the Union achieved mixed results in achieving this kind of equality among its 1,000 members over the years.

The former Babcock home at the coner of Delaware Avenue and Niagara Square (site of the City Court building), shortly after it became the first home of the Women's Union. Image source:TBHM

The Women's Union c. 1890. Image source: private collection

View of the Women's Union and the adjacent Working Boys Home across Niagara Square, c. 1910. Image source: TBHM

From the start, wealthy members secured the financial support of the Union's goals from their husbands. Successful men in Buffalo were invited as speakers on various topics of enrichment. Ellie Josephine Shepard said in 1918, said "A list of lawyers who acted as counselors to the Union would include nearly every prominent attorney in Buffalo."

The Union educated its members on navigating the bureaucracies of government in order to achieve reform. Locally, it was able to secure a permanent position for female police matron. On the state level, the Union lobbied successfully for a number of years for a state law establishing equal guardianship rights for women in the case of divorce. The Union succeeded in having a woman appointed to the Buffalo Board of School Examiners (school board).

The Union also aggressively pursued in court unpaid wages owed to servants, tutors, and private instructors by employers, succeeding to the extant that the mere mention of the Union became sufficient to elicit the funds owed.

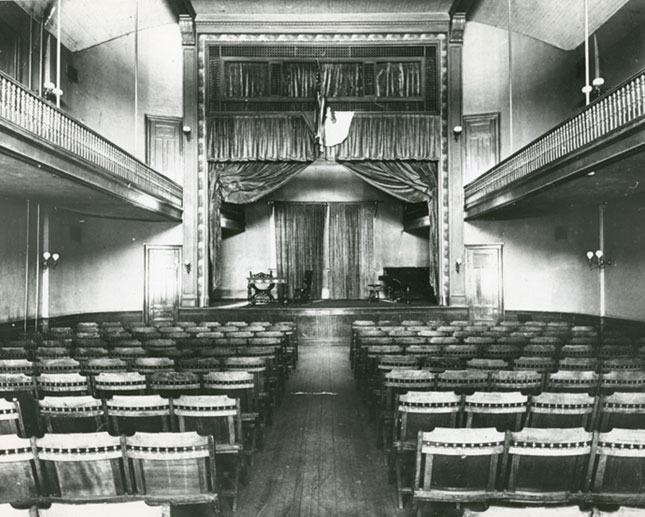

The auditorium. Image source: TBHM

Attending to the needs of small children, the Union opened "kitchen garden" classes for girls from age seven to fourteen. The program instructed the girls,most of whom were immigrants, in housekeeping activities in a play-like atmosphere. They were provided with lunch. Eventually, due to popular demand, some boys were admitted to these programs.

When Harriet Townsend received praise for her her with the Union, she always answered, "Oh, no, it wasn't Mrs. Townsend who did that, it was the Union."

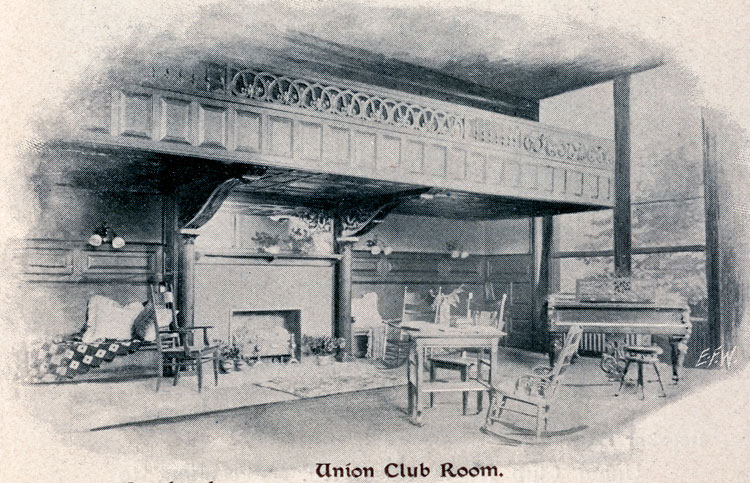

Image source: TBHM

The Union was the headquarters for any visiting women's organization and, during the Pan-American, served the National Association of Colored Women, the Nurses Association, State Federation of Women's Clubs, Household Economic Association.

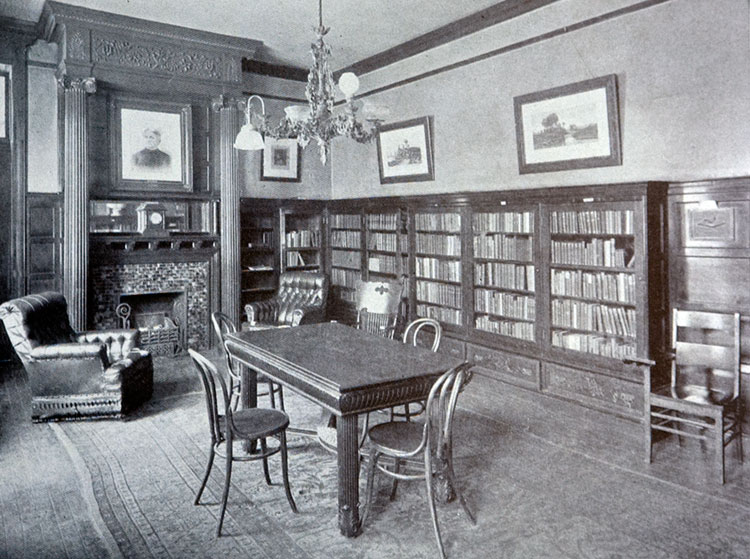

The Mary Ripley Library in the Union Building. It had 500 reference book and subsribed to a score of periodicals.

Image source: UB Archives

The Union voted to dissolve in 1915, observing that its work was finished. Most of its ground-breaking programs had been adopted by educational, governmental and civic organizations, including vocational education, physical education, night schools, free kindergartens, probation officers, Legal Aid, etc. Everything the Union did needed to be done, and Harriet Townsend and her Union members did it first.

At the last meeting, Union president Mrs. Elizabeth Howe said, "Rarely has an institution been so preponderantly the expression of a single personality as has the Women's Union been of Mrs. Townsend...this building is a place of ghosts...and pervading all the indomitable will, the glowing personality, the spiritual radiance of the Union's founder and leader, Mrs. Townsend." One obituary writer said, "her name was in Buffalo through a long period almost a household word." Prominent, intelligent, strong-minded Buffalo women had served the Women's Union, but none had the confidence and charisma of Harriet Townsend to lead the organization for most of its lifetime. Her leadership held the organization together and kept it financially solvent, her diplomacy prevented the hot-button suffrage issue from derailing the organization. Her "sunny presence and encouragement" were felt as a "keen personal loss" by those privileged to work with her. |

Townsend Hall entrance hall. Image source: TBHM

The Union sold the building to the University of Buffalo with the provision that the building be called Townsend Hall. It became the University’s first College of Arts and Sciences. At the ceremony marking the formal presentation of the building to the University of Buffalo in 1915, Chancellor Charles P. Norton said of Harriet Townsend, "The Women's Union has founded the University; here is the woman who founded the Union."

Townsend Hall. Image source: TBHM

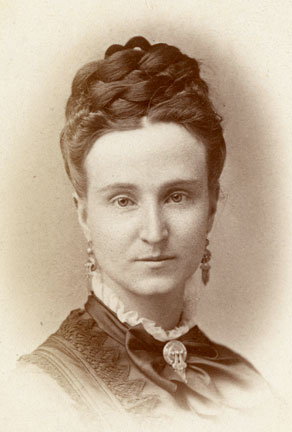

Harriet Townsend as a young woman.

Harriet Townsend as a young woman. Harriet Townsend in middle age.

Harriet Townsend in middle age.