Influenza on the Homefront (Part 4 Epilogue)

The pandemic in Western New York peaked around October 20 when 138 residents of Buffalo and Erie County died on that day. Funerals were conducted as "drive-bys," with priests blessing a stream of caskets as they passed in front of the church. At St. Stanilaus Cemetery, where most Polish residents were buried, coffins (and even bodies) were left in the open awaiting burial. When the city ordered prompt burial, the cemetery hired 35 additional grave diggers and purchased new digging machines.

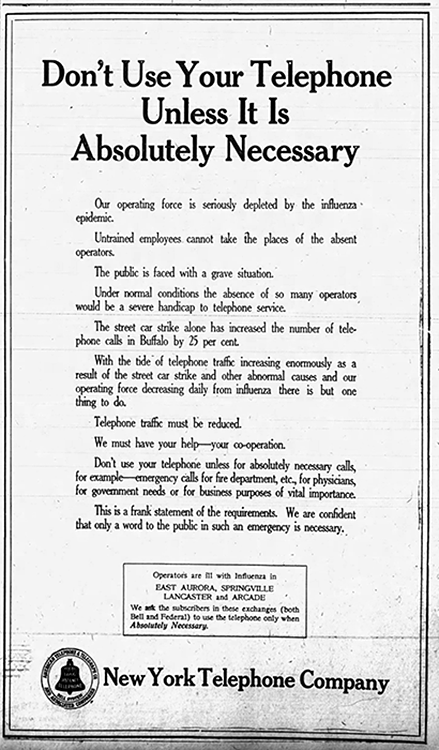

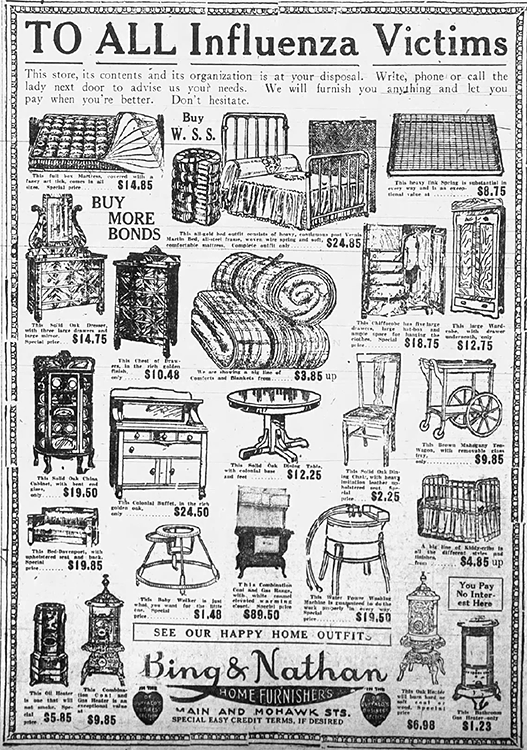

The telephone system suffered as subscribers reached out to their friends and families during the quarantine. Bing & Nathan's department store encouraged the homebound to buy now and pay when healthy.

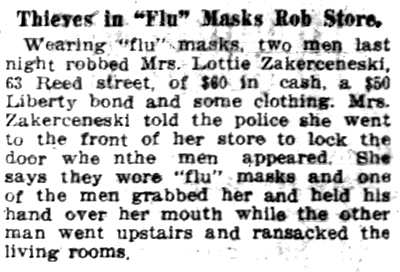

The mask-wearing habit inspired two men to utilize them in a robbery on October 26.

The mask-wearing habit inspired two men to utilize them in a robbery on October 26.

Buffalo was fortunate to have endured the outbreak weeks later than other cities such as Boston and Philadelphia and was able to choose best practices from those experiences. Dr. Franklin Gram's leadership as acting health commissioner was aided by his select advisory committee. They formed a program that proved successful in limiting the spread of influenza by mobilizing available resources, restricting movements of the public, investigating and enumerating the spread of the disease, and public education. The education was accomplished by newspaper advertisement, posters, payroll circulars and distribution of information through physicians. Part of the emphasis was on avoiding contact with others. Dr. Gram said, "Stop shaking hands! Even at the expense of appearing discourteous, don't do it!"

Although Western New Yorkers would continue to sicken and die from influenza well into 1919, the number of new cases dropped so that the city's quarantine was ended early in November. The entire effort took a toll on Dr. Gram who had to step away from his duties for a rest due to high blood pressure.

In March 1919, Dr. Gram submitted his official report on the pandemic. In the city there had been 32,451 cases of influenza reported, with a total of 2,806 deaths from influenza and pneumonia. The city health department had spent $75,000 to fight the pandemic ($1,294,679 in 2019 dollars). No one summarized the cost to area businesses during the autumn of 1918.

The death toll of U.S. soldiers from influenza was profound. For every 100 soldiers that died in combat, 102 died from influenza.

This series ends on a personal note. My great uncle, Glenn Eck, served in WW1 in Europe with the 335th Field Artillery regiment. He was engaged to a 25 year-old teacher named Anna Bohn who lived in Sheldon, NY. Where he might have died in the Meuse-Argonne or from influenza, it was his fiance who died instead from the disease. Sixty-five years later, Glenn Eck's great nephew (my brother Nate) married Anna Bohn's great niece, Sandy Bohn. The two families were united after all.

This series ends on a personal note. My great uncle, Glenn Eck, served in WW1 in Europe with the 335th Field Artillery regiment. He was engaged to a 25 year-old teacher named Anna Bohn who lived in Sheldon, NY. Where he might have died in the Meuse-Argonne or from influenza, it was his fiance who died instead from the disease. Sixty-five years later, Glenn Eck's great nephew (my brother Nate) married Anna Bohn's great niece, Sandy Bohn. The two families were united after all.

One of the resources used for this series was Deborah Bruch Bucki's excellent paper, "A History of Buffalo's Medical Response to the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919."