Not Done Yet: Buffalo Mansions on Duty in WW1

When World War 1 began in July, 1914, Buffalonians began to organize war relief work for civilians suffering in France and Belgium. In 1915, two local organizations merged into American Red Cross Buffalo War Relief and Workrooms Committee; Ansley Wilcox was chairman. Then, in July 1916, amidst the "Preparedness" imperative sweeping the country, the Buffalo chapter of the American Red Cross was formed, eclipsing previous organizations. Headquarters were in the Root building, 70 West Chippewa. Several committees were appointed. All that remained was a declaration of war by the United States, which came in April, 1917.

Mobilization of Red Cross committees, establishment of local branches and auxiliaries, proceeded with great speed. By war's end, Buffalo had five workrooms and 45 more in Erie County; they produced medical supplies and clothing. Erie County had 78 Red Cross branches and 132 auxiliaries, 60% of which met in churches, 40% in clubs. A popular tagline urged: "Everybody must be up and doing."

Although workrooms were established in some vacant storefronts, on the 4th floor of Hengerer's Department store, the 5th Floor of the Niagara Life Building, and an entire floor at the Sidway building, the Buffalo Red Cross hit the jackpot when four vacant mansions were made available. Here is their story.

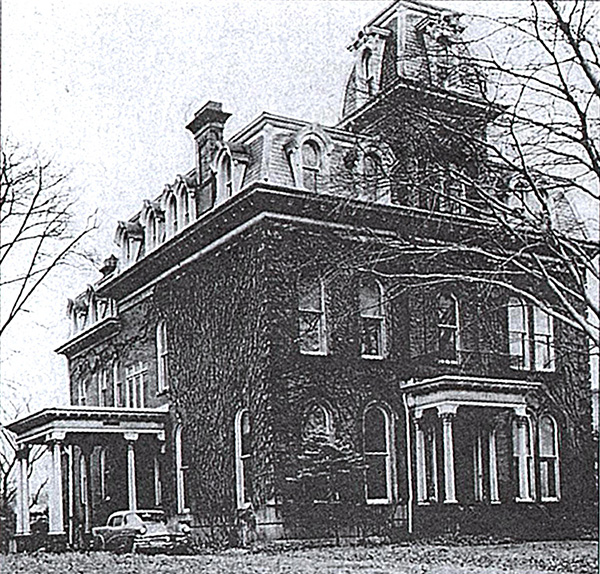

The Gratwick Mansion, 776 Delaware Avenue

Designed by H.H. Richardson and constructed in 1888, the great brownstone mansion was owned by lumber millionaire William H. Gratwick. He died in 1899; his widow Martha lived until her death in July,1916.

In April, 1917, the month war was declared, the family turned the house over to the Red Cross. It became the Buffalo headquarters for miliary relief, turning out surgical dressings, bed linens, hospital garments, socks and a "mulitude" of other items needed in U.S. field hospitals in the war zone.

The size of the house also permitted classes held for local residents in home nursing. When the Buffalo Red Cross organized Base Hospital 23 prior to its departure for France, its nurses, doctors and civilian staff took French classes in the mansion.

The mansion was one of two centers for the packing and shipping of items. By war's end, 5,000 cases of supplies had been sent from Buffalo.

After the war ended in 1918, the house was vacant until the family demolished it in October, 1919.

The Altman-Daniels Mansion 787 Delaware

Constructed in 1869 by Abraham Altman, by the late 1880's it was owned by Judge Charles Daniels and his wife. His widow, Mary, died in 1917, and the vacant house was available to the Red Cross. The entire house was converted to the making of surgical dressings, which had to be accomplished under strict, hygenic practices.

The American Red Cross created uniforms for every type of employee or volunteer. The "workroom" uniform consisted of a "large white apron, fastening in the back, with sleeves to the wrist and a V or square neck. Belt three inches wide; two pockets in the skirt. Red cross, two inches square, may be worn in the front of the base of the neck. A veil of batiste or some such material. The veil is red, white, or dark blue...Workers [vs. heads of workrooms] wear a white veil with a white band."

Daniels' mansion dining room workroom; the chandelier had been converted to electricity only recently

The Altman-Daniels mansion had a third life after the war; grandson Charlie Daniels and his wife, Florence Goodyear, purchased it in 1921, made extensive renovations and enjoyed it until having it demolished in 1931 to save taxes.

The Doty Mansion 795 Delaware

David Bell had the mansard-roofed mansion constructed in 1872. It featured Carrera marble, a large entry hall with elaborate staircase, a third floor ballroom. By the end of that decade it was purchased by Leonidas Doty, a banker and railroad magnate. He died in 1888; his widow Salina lived there until her death 1915. The house became vacant and served various functions during the war. It was the headquarters for foreign and civilian relief. In 1917, it featured nationality workdays; one day those of French birth or ancestry were invited, another day those of Italian birth, and another day for Canadian descendents. The committee collected clothing for shipping abroad to war-torn areas and assisted in making surgical dressings.

David Bell had the mansard-roofed mansion constructed in 1872. It featured Carrera marble, a large entry hall with elaborate staircase, a third floor ballroom. By the end of that decade it was purchased by Leonidas Doty, a banker and railroad magnate. He died in 1888; his widow Salina lived there until her death 1915. The house became vacant and served various functions during the war. It was the headquarters for foreign and civilian relief. In 1917, it featured nationality workdays; one day those of French birth or ancestry were invited, another day those of Italian birth, and another day for Canadian descendents. The committee collected clothing for shipping abroad to war-torn areas and assisted in making surgical dressings.

The Doty mansion had a long life after the war. It was purchased by Gowanda's Richard Wilhelm and his wife as their city home. After her husband died in 1940, widow Alice Wilhelm left the house vacant for the next 15 years. It was demolished in 1956 in anticipation of construction of a 75-unit motel. (That did not happen; the property is now part of the Jewish Community Center campus.)

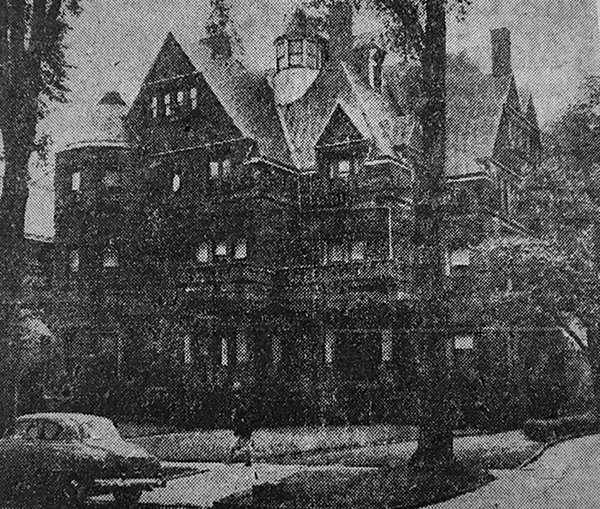

The Jewett-Greene Mansion 303 North Street

The Jewett-Greene Mansion 303 North Street

Josiah Jewett, banker, built the massive mansion on North Street for his wife and six children in 1883. They enjoyed the home for 30 years, with its double-paned windows, sub basement, and large rooms beautifully appointed. In 1904, it was sold to General Francis V. Greene, who lived there until leaving Buffalo in 1915. The vacant home was available for use by the Red Cross during WW1.

It was one of two headquarters for packing and shipping. The second and third floors were devoted entirely to creating "front line parcels," what we would call field dressings. Assembled were sterilized cotton daubs for wound cleaning, swabs for probing if necessary, drainage tube, gauze compresses, absorbent cotton dressing with long strips of linen to hold dressings in place during the journey to the field hospital.

On December 6, 1917, the Buffalo Red Cross was ordered to send 20,000 frontline packages containing 220,000 surgical dressings before Christmas. That effort translated into 50,000 dressings a week or eight times the normal production. Newspaper articles repeated calls for volunteers to help at all workrooms in the city and surroundings. The work was ordinarily performed by women, but a special effort was put forth by 50 volunteers from the Buffalo Club; the Knights of Columbus manned the electric cutting machines, and the University Club and Rotary Club assisted on assigned evenings. Buffalo's production exceeded the requirement.

The Jewett-Greene mansion had a long life after the war when it was sold to the Buffalo Diocese for occupation by the Sisters of Mercy. They renamed the house "Casa Misericordia." In 1952, three nuns and 22 students resided there. It was said that the bedrooms were so large that dividing them in half created comfortably-sized bedrooms.

The home was demolished in 1971 and replaced with the Symphony North Apartments, advertsied as "luxury furnished studio apartments."

A workroom in Buffalo

A workroom in Buffalo

A workroom in Buffalo. Image source: Library of Congress

Knitters across the county fell to work making gloves, socks, sweaters, balaclavas throughout the war for distribution to soldiers. The American Red Cross noted that a if knitter completed 30 stitches a minute on average, 11 hours 38 minutes of steady work was required for one pair of socks. The Buffalo draftees at left are adorned with handmade balaclavas, sweaters and vests as they board a train to leave for training camp.

Careful statistics were kept throughout the war years of the production of surgical dressings, comfort kits, hospital clothing and patient supplies, clothing and bedding for civilians, etc. The total number of pieces made and sent to the war zone from Buffalo and Erie County was 2,975,486, valued in 1919 dollars at $1,100,888.96.

The war effort brought together, working as equals, prominent men and women working side by side, middle class and working women, native and immigrant, suffrage and anti-suffrage in a united effort for a national cause. It was accomplished through "meatless" days and "wheatless" days and Buffalo winters with scarce coal. Cooks learned to use corn syrup instead of sugar, gardeners taught classes in growing and preserving food. And Western New York, like the rest of the country and those in uniform, suffered during the global pandemic that was influenza.